While there are some great pockets of work taking place to deliver better public services, the UK government’s overall attempts at technology-enabled, or “e-government” or “digital”, reform appear to be struggling to achieve and sustain the benefits promised at the pace and scale originally foreseen. And not for the first time – this has been a repeating cycle of optimism and disillusionment since the mid-1990s. So why is this?

The 3 wellsprings

To understand what’s worked, and what hasn’t, I’m going to look at 3 of the major influences on the digital reform programme of the coalition government of 2010-2015, and of the successor Conservative administrations since 2015:

- Better for Less (2009) – which helped develop the policies of open data, innovate/leverage/commoditise, disaggregation, spend controls, open standards, SME-focus, service-oriented / micro-services architecture, cloud first / buy before build, etc.

- Directgov 2010 and beyond: revolution not evolution (2010) – which helped accelerate the website convergence onto GOV.UK already underway as part of Directgov, and which set out ambitious plans to open up government through the widespread adoption of APIs (application programming interfaces – interfaces to provide access to government systems)

- The House of Commons Public Account Select Committee’s (PASC) report into Government IT (2011) – which supported the move towards opening up the market, re-skilling the civil service and the increased use of SMEs.

I’m well aware of course these weren’t the only contributors. The run-up to the general election of 2010 was a rich period of innovation and ideas, including the long-since defunct Make IT Better Conservative website and the Ideal Government IT Strategy – imaginative crowd-sourced ideas which were socialised and discussed with each of the three main UK national political parties. There was also the series of joint Design Council and London School of Economics (LSE) events in 2011, looking at how improved service design could play a significant impact in improving the experience of public services in the specific area of social security (welfare), both for those offline and online (my own small contribution to that can be seen here).

I’m not ignoring these many other efforts, all of which helped shape and influence the landscape. But it’s these 3 specific wellsprings of the recent digital reform movement I want to explore in order to understand what has worked and what hasn’t.

But first … the backstory

It’s important to understand that the 2010 reform programme didn’t start with a blank page. The focus on users (“user needs”) and outcomes (rather than simply putting existing transactions and services online) goes back to the 1990s. The UK government has been in the vanguard of trying to use technology to reform public services since at least 1996 and the publication of Government Direct. A Prospectus for the Electronic Delivery of Government Services.

However, it was the Labour administration from 1997 onwards that broke significant new ground. It reset the focus on outcomes based on citizens’ needs instead of propagating online the siloed government departments and agencies involved in their delivery. It recognised that:

Part of this transition was the focus on “life episodes”, developed by extensive research with the users of services and focused on meeting their needs.

The research that went into these life episodes identified six initial services that were prioritised first:

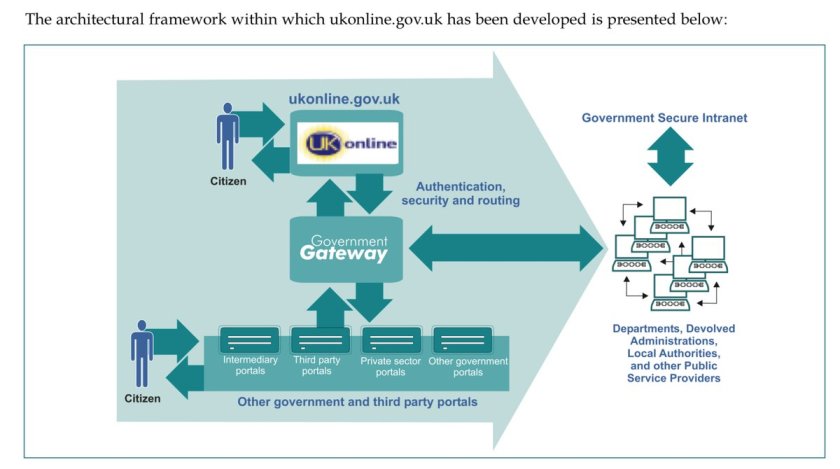

Behind the scenes, these new life episodes were implemented via two cross-government platforms – the ukonline.gov.uk website; and the authentication, security and smart routing and orchestration facilities provided by the Government Gateway.

Impact

This approach – undertaking extensive research into users’ needs, rebuilding services around life episodes that spanned multiple departments and agencies – was a refreshing change from the earlier approach of simply putting silo existing transactions online. And the development and use of common cross-government platforms and infrastructure helped put the UK government at that time at the forefront of innovative reform.

The justification for adopting common, cross-government platforms was explained as follows:

“[this approach] was designed to simplify and accelerate the UK e-Government programme. It achieves this by ensuring that the common building-block components of e-Government services are provided once, in a flexible, modular and scalable way.”

[Source: “Delivering e-Government Services to Citizens and Businesses: The Government Gateway Concept”. Jan Sebek, p.127. Published in “Electronic Government: Second International Conference, EGOV 2003, Volume 2”. Editor Roland Traunmüller]

A 2002 report noted that

The UK has been in the vanguard of developing common IT architectures, and was ahead of most of the benchmark group in developing the IT core to enable secure transactions with citizens … [However] If the UK government is to achieve targets around online service delivery and e-procurement then significant progress will need to be made in standardising systems between departments. This investment need is particularly acute at the level of local government.

These remain valid observations. Whilst the UK had successfully pioneered common platforms at the centre of government, their success would depend upon the discipline of opening up and standardising the way government works rather than each part thinking itself “special” and home-baking its own bespoke local approach. At the local government level this issue is still particularly problematic and difficult to tackle, with large scale duplication of resources, technology, systems and processes and little effective momentum towards the adoption of platforms to meet the needs shared in common by every council (part of the issue discussed in the recent Better Public Services Green Paper [PDF]).

By around 2003, this cross-government platform model had developed into a range of common components to help build services in a consistent and cost-effective way. They included:

- Cross-government website: providing a single point of entry to services and information, oriented around extensive user research and collating users’ needs into life episodes

- Registration and Enrolment: the identification, authentication and verification of online users — citizens, businesses and intermediaries — utilising a range of credentials, from user ID and passwords to digital certificates to — later — EMV chip and PIN cards

- Transaction Engine: handling the processing of transactions between citizens, businesses and departments, including the management of state and orchestration across multiple organisations to support the joined-up life episodes

- Secure Messaging: handling two-way secure communication between departments and citizens

- Payments Engine: handling in-bound payments to government departments

- Helpdesk: an internal service enabling departments to integrate a degree of management of these common components services within their existing helpdesk services

Building on the shoulders …

The 2010 reform programme inherited this environment of user-focused services and cross-government platforms. It was ideally placed to build rapidly on the shoulders of what was already in place, and to take reform to the next stage – by focusing on a more fundamental de-siloing and redesign of government itself, enabled by the user-centric redesign of better outcomes and supported by cross-government platform delivery.

This is the soil in which the seeds of the subsequent reforms from 2010 onwards had the perfect opportunity to grow. I’ll be exploring how well they were nurtured and how well they’ve flourished in my next blog in this mini-series.

Original source – new tech observations from a UK perspective (ntouk)